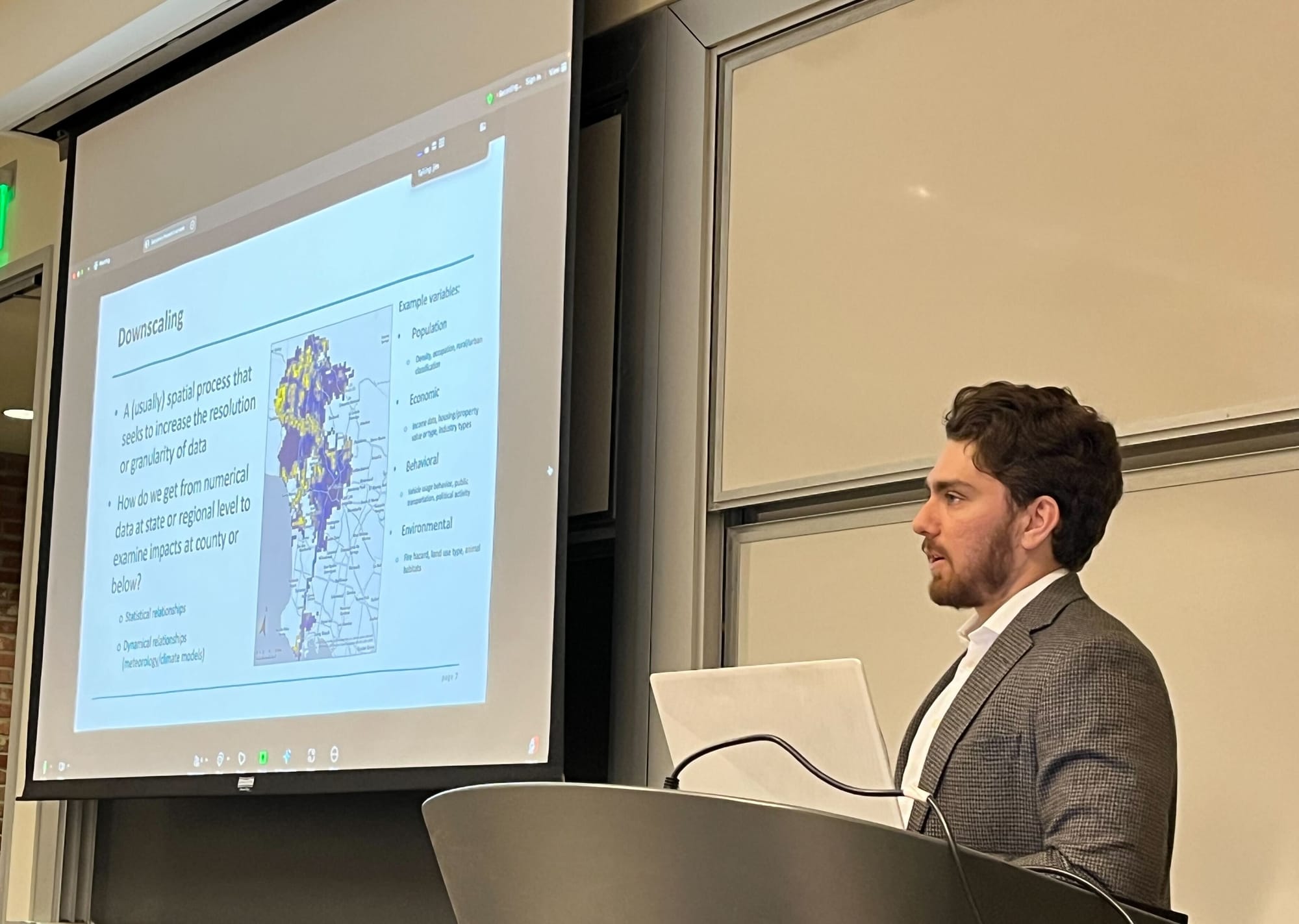

Spotlight: Benjamin Preneta

Senior Analyst and former Summer Fellow at Evolved, Benjamin Preneta, brings a cross-sector mindset and geospatial fluency to downscaling, a tool that helps turn big-picture energy plans into real-world actions.

Planning, Place, and the Power of Maps

The Polish forest stayed light until 10 p.m. in the summer. Most nights, after tank training drills, Ben Preneta would lace up his shoes and run through the woods — a rare calm in a high-pressure role as an armor officer stationed in Eastern Europe. His intuitive understanding of land — developed through a childhood in Northern California’s backcountry, military maneuvers across uncharted terrain, and long-distance trail runs — would later inform his approach to a deceptively complex question: where, specifically, should all this clean energy actually get built?

Today, Preneta is helping build one of the most quietly transformative innovations in modern energy modeling: downscaling - a technique of representing possible energy futures down to a granular level on a map.

His process is shaped by a recurring tension — a desire to connect abstract aspirations with grounded realities. Whether navigating military operations or modeling climate futures, Preneta has always been drawn to the hard work of implementation: where lofty theoretical possibilities meet the logistical constraints of real-world obstacles.

At Evolved Energy Research, downscaling is more than a technical method. It’s a philosophy and a storytelling tool — one that translates national and regional energy models into fine-grained, human-readable maps and analyses. These maps don’t just show where energy might go; they illuminate the tradeoffs, the tensions, and the possibilities embedded in the energy transition.

“It’s one thing to say, 'We need this much solar by 2045,' and another thing to show where that might actually go,” Preneta explains. “That’s where people start to care. That’s where real-world concerns influence policy, and where compromise takes place.”

From Tanks to Terrain

Preneta’s time in the military gave him more than logistical acuity—it offered a rare perspective on systems, service, and the value of operating across sectors. He often reflects on how siloed his chosen areas of service have become—how the military and the climate world are often culturally and politically separated, despite both aiming to serve the common good.

"The military shouldn’t be a politicized organization. Solving climate change shouldn’t be politicized either. These are things that, when applied correctly, serve the common good."

This belief of bridging seemingly distant worlds to generate real impact has become instrumental in his career.

Preneta’s path into energy modeling is as layered as the GIS maps he now creates. Raised in Berkeley and Ukiah, California, his early connection to the outdoors gave him an innate curiosity of how people interact with their surroundings.

"I've always been drawn to the outdoors, and I think that spurred part of my interest in maps and understanding how we physically relate to space. As we get more connected in different ways and our world gets more complex, we often forget just how important the impact of place and the relationship to geographic space is."

As an undergrad at Columbia, he studied modern African history, focusing on post-colonial governance and peacekeeping, while also pursuing sustainable development. It was a dual lens: human systems and earth systems. Their frictions and overlaps intrigued him.

Preneta participated in ROTC during college, and he was commissioned as an armor officer in the US Army after graduating, serving for four years. Stationed in Poland during COVID, his platoon trained in the woods for months, isolated from local towns but immersed in landscape.

“When you’re maneuvering tanks, geography is everything,” he recalls. “But it also reinforced the foundation of connection to place."

Later, as a company executive officer, he handled logistics for over 100 soldiers and millions of dollars in military equipment. He was regularly tasked with taking strategic intent and turning it into concrete action—what terrain they would train on, what materials were needed, and what deadlines had to be met. As he grew adept at translating strategic intent into operational plans, he began to reflect on the kinds of problems he found most meaningful—and the contexts in which solutions felt most tangible.

"I had long considered the complexities of the existential crisis of our time," he reflects. "And I kept feeling pulled to energy and climate."

A Pivot at Columbia

Returning to Columbia, this time to the Climate School’s MA in Climate and Society program, Preneta pivoted into climate science, GIS, and atmospheric dynamics. But even in academia, he felt the familiar challenge of bridging large-scale thinking with tangible solutions—a theme that would soon find resolution in downscaling.

“It was like a bridge for me—from humanities and systems thinking into technical tools and modeling.”

There, he found a listing for a summer fellowship project with Evolved Energy Research. The task at hand: investigate the feasibility of “energy parks”—co-located renewable generation and clean fuel production.

“We were talking about infrastructure that didn’t exist yet. The challenge was: Where would it make sense to build it? And what geographic variables matter most?"

He turned to GIS-based raster analysis and focal statistics, layering land suitability, transmission access, and industrial potential to locate the best potential sites.

“That was my first real exposure to downscaling in practice,” he noted.

Making the Energy Transition Legible

For Preneta, downscaling offers a kind of resolution to the mismatch he'd long observed between vision and execution. It is the rare technical tool that doesn’t just describe a possible future—it asks how to make it possible and what could be the effects. Although downscaling is not a replacement for site-specific suitability studies, it adds a much-needed relatability to the modeling results.

"So much of what we do as modelers, planners, or strategists stays at the vision level. But someone has to figure out how to build it—where to put it, how it fits with the land, with the people who live there. That’s what drew me in."

Downscaling, at its core, is a method of taking outputs from capacity expansion models—often at the national or regional level—and translating them into finer geographic resolutions that reflect the physical, political, and social realities of the ground. It grew from a need to make these large-scale plans more tangible: not just how much energy will be needed, but where it might be sited, what land it might occupy, and who it might affect.

"There's a lot of great modeling out there," Preneta argues, "but without geography, it can feel abstract. Downscaling helps us bring that into the real world. It takes those big numbers and asks: what does that actually mean for this county, or this stretch of farmland, or this substation?"

Downscaling requires not only technical modeling expertise but a fluency in GIS tools, coding, regulatory constraints, land use trends, and stakeholder needs. It was a natural fit for someone with Preneta's diverse background.

Now a full-time team member at Evolved, Preneta is central to some of the firm’s most impactful downscaling work, such as the Annual Decarbonization Perspectives (ADPs).

“Downscaling is about making the energy transition legible,” he emphasizes. “We start with high-level model outputs—and ask, what does that look like on the ground?"

In the ongoing project, Power of Place: New York, Evolved is mapping realistic renewable development areas using constraints like flood zones, conservation areas, and local ordinances. Then they layer in cost, population density, and least-cost transmission paths.

“You might see a scenario that calls for 10 gigawatts of solar,” he proposes. “But where? What kind of land does that impact? How close is it to population centers or transmission lines? That’s what downscaling seeks to answer.”

These maps are now being used by policymakers, planners, and utilities to inform decisions and evaluate the trade-offs of different scenarios.

“The maps make it more real. You’re no longer just looking at numbers in a spreadsheet. You're seeing what it means for farmland, or forests, or people’s homes."

Evolved’s Middle Ground

The same ethos that drew Preneta to military service—working through differences in pursuit of collective progress—continues to animate his work in the energy world. At Evolved, he sees his cross-sector fluency as an asset, not an anomaly.

"Breaking down silos between service sectors—military, climate, environmentalism—is critical. And it’s possible," he stresses.

Preneta’s interest in downscaling is, in many ways, an extension of a deeper theme that runs through his career: the tension between abstract planning and grounded implementation. In the military, he was often tasked with translating strategic goals into real-world logistics under pressure. At Columbia, he wrestled with theoretical models that lacked real-world resolution. Downscaling offered something different: a way to reconcile those poles.

“So much of what I’ve done has been trying to bridge that gap between vision and reality. Downscaling is one of the best tools I’ve seen for doing that—because it asks you to engage with constraints, with geography, with politics, and with people.”

One of the reasons Preneta feels at home at Evolved is its position between academia and implementation. The company’s consulting model allows for deep research, but with the urgency and responsiveness required by real-world planning.

“At Evolved, I get to work at this boundary between theory and action. We're not just modeling a future. We're helping make it legible—and hopefully more just.”

He appreciates the team’s diversity of skills and perspectives, as well as the shared commitment to producing rigorous, decision-useful tools. Navigating this challenge is especially relevant to downscaling, where results must be actionable but not overly prescriptive — highlighting tradeoffs and variables rather than a determined future.

“We’re not in an ivory tower. But we’re also not selling snake oil. It’s a space where complexity is welcome—and necessary."

Looking Ahead

Two frontiers excite Preneta most: demand-side downscaling and applications in the Global South.

On the demand side, he’s working with utilities to predict where electricity use will rise fastest—not just by sector, but by substation, neighborhood, or zip code.

“Same principle: high-level forecast, local implications. It helps utilities plan where to invest, where to upgrade, where to prepare."

And in the long term, he sees a role for downscaling in places that haven’t yet built full energy systems or are still in the process of developing them.

“If you're operating in a resource-constrained environment, you can’t afford big mistakes,” he adds. “Better planning tools could change the game."

The Layered View

In many ways, Preneta’s career is itself a kind of layered map.

“My narrative, as [Evolved Senior Research Fellow] Jim Williams once described it, is all about layering: outdoor experience, understanding human systems in history, finding applications and strategic problem solving in the military, incorporating the physical world through climate science, and finally using GIS as the lens through which to understand. Each layer helps make sense of the others, which is fundamental to energy systems that permeate so widely."

It’s no surprise, then, that downscaling has become both his toolset and his metaphor.

“Downscaling is a tool,” he posits. “But it’s also a philosophy. If we can see clearly what change might look like — at the level of towns, neighborhoods, even individual parcels of land — we have a better shot at doing it well."

Thanks to his work, the energy transition is becoming clearer — not just from above, but from the ground up.